He mocks it himself as a “nursery rhyme” name, which is a nice bit of misdirection from what’s actually a name befitting classical allegories like Everyman or Pilgrim’s Progress, both of which are relevant here. Let’s pause to consider this Peter and his phallic world, and let’s start with his name. Disappointed and fed up, Nora leaves him by saying she hopes he’ll find what he’s looking for - “Or do I?”

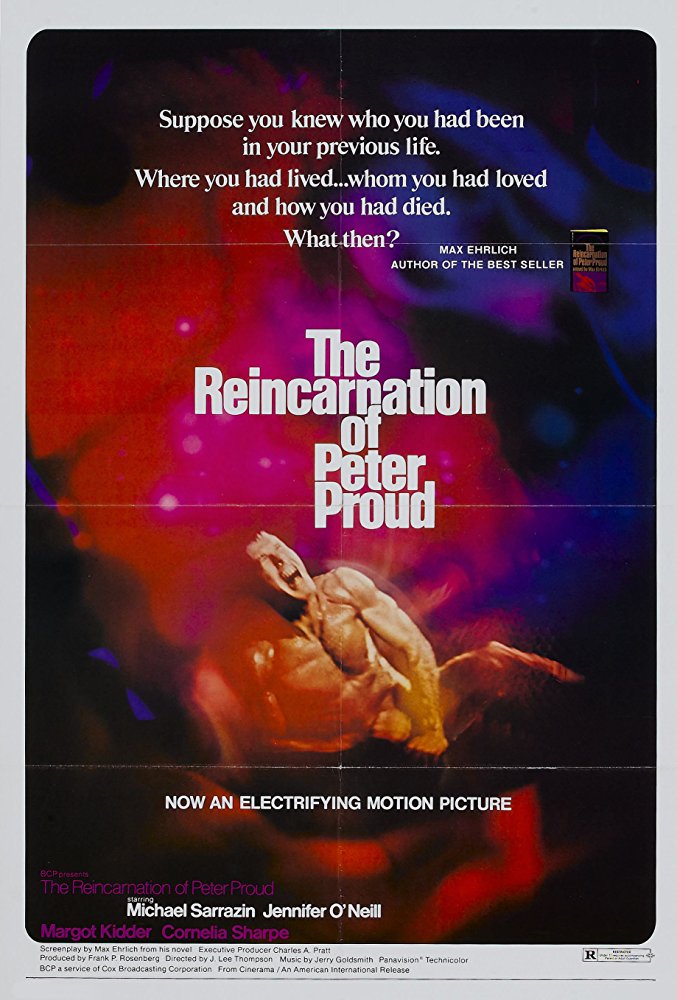

After false starts with various medical professionals, Peter comes to believe he’s reliving snippets of a previous life from somewhere in 1940s Massachusetts, and he sets off, as the era’s phraseology had it, to find himself. Peter’s been haunted by these vivid recurring dreams for months: always a festival of jump cuts starring pretty women, lavish consumption, a snazzy car, and insistently phallic landmarks: posts, spires, gables. She’s as nude as he is, for this is a movie full of casual nudity and constant erotic teasing, even though only one bathtub scene indulges full frontal. That hero, Peter Proud (Michael Sarrazin), sweating and thrashing and calling in his sleep, is awakened by his down-to-earth girlfriend Nora (Cornelia Sharpe). He’ll never make it to the glittering promise of the Puritan, but wasn’t that an earthly delusion after all?Īll this time, amid the flurry of disorienting jump cuts, the water and night and nudity and violence, Jerry Goldsmith‘s score orchestrates a nervous, modernist sound that will haunt this entire slow-burning movie as its hero follows a path that spirals in upon itself like a whirlpool. She bashes him with the oar and he sinks to the bottom. His head floating in the black water, the man calls her Marcia and apologizes for what he just said, explaining that he was drunk and didn’t mean it, that he loves her. A tearful, fearful young woman in a rowboat emerges from the fog to meet him.

A naked man, at night, dives into a lake and sluices across the water toward The Puritan Hotel, a loaded name for any bare pilgrim. In dreams begin responsibilities, and often movies. Maybe it’s even a spoiler to discuss the beginning. We can’t help it, so this whole review may be a kind of SPOILER. It’s impossible to discuss the film without addressing that ending, for this is among those rare movies entirely made by their end, as if they’d been working backwards from that point. As archetypal an example of the mythological and psychological concept of the “eternal return” as you’ll find in cinema, the finalé orchestrates events into a helpless flow that, in retrospect, can only feel right, had always felt right, will always feel right.

I first saw it on a commercial broadcast so censored and dark that it couldn’t make much impact beyond its ending, but that ending is unforgettable. There’s something about The Reincarnation of Peter Proud that keeps it lodged in the memory like a nasty splinter.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)